A Week Chasing Tornadoes

In high school, I asked my friend Jim why his AOL screen name was “wxmann”. He explained that it stood for “weatherman”, and he’d picked it because he loved the weather. I voiced my assumption that he wanted to work as a meteorologist after school, but he laughed and said, no, he was going to get a job that actually paid well.

A decade later, Jim is happily employed as a software engineer in San Francisco, and he still loves the weather. When tornado conditions suddenly developed on the Great Plains, he publicly deliberated, on Twitter, whether or not to go tornado chasing on the spur of the moment. I texted him to say I’d go with him, and so, at 1am a couple of days later, we boarded a budget redeye flight to Denver, with a rental car waiting for us when we arrived.

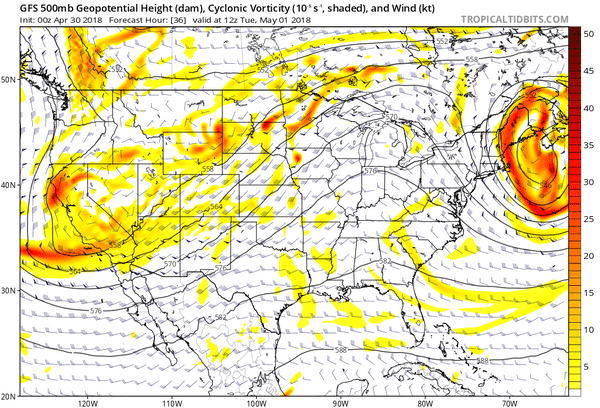

Jim didn’t just take me storm chasing, he also completely changed the way I think about the weather. As we waited at baggage claim, groggy after three hours of sleep on cheap plane seats, he pulled up this image on his laptop:

“So this big weather pattern,” he gestured, “is causing the recent cold snap in the Bay Area. But on the east side, on the Great Plains, it’s pulling in warm moist air from the Gulf of Mexico, which along with the strong upper-level winds create the wind shear required for tornadoes to form.” I’d never thought about how different weather conditions around the country are created by the same large weather systems, which, in a sense, connect the distant places.

I’ve always thought of the weather as a random, uncontrollable condition of my environment at a given time. It might be windy, or rainy, or cloudy; there may be lightning or snow. It isn’t really predictable or manageable in any way except by wearing appropriate clothing, and perhaps waiting for conditions to change.

On this trip, I learned to see the weather as something I could engage with. I don’t have to be passive; the weather doesn’t have to just happen to me. I can take an active role in my experience of the weather. This fundamental shift comes from two tools: real-time weather data, and a car.

Jim has an app on his phone called RadarScope that displays real-time weather data, letting you zoom out and see the storm from a broader perspective. When you’re in the storm you’re at the wrong scale; it seems so big that you can’t really perceive it as an object. But zoom out and view it on radar, and you can see that the storm has borders, and a core, and is moving at a certain speed in a certain direction. Suddenly the storm is small enough to comprehend.

A car, along with a good road network like the one in Kansas, lets you act on that information. The storms we tracked moved at roughly 40mph, so we were able to keep comfortably ahead of them.

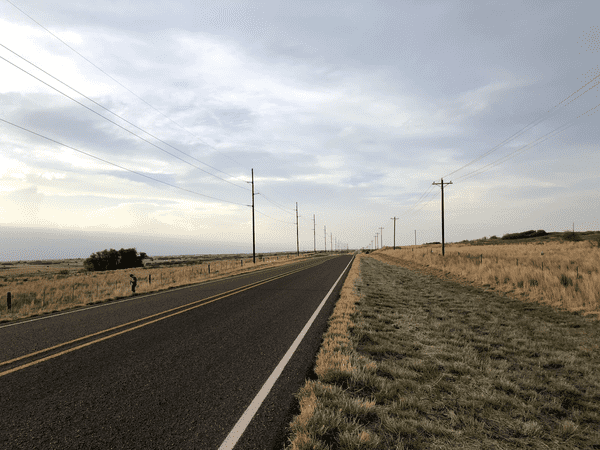

A typical day went like this: in the morning, Jim would identify an area where storms might develop tornadoes, and we would drive for three or four hours to get there. Then we’d camp out at a local library or cafe and do some work in the afternoon. Around 4pm, storms start picking up. That’s when you can see them on radar and get a sense of where they’re moving and which ones are likely to generate tornadoes. At this point, we’d kick into high gear and drive for about an hour to the nearest tornado.

With me behind the wheel and Jim keeping an eye on the weather radar and observations, for the next three or four hours we would track the tornado. It goes the way I imagine stalking big game, except on the scale of dozens of miles. We’d pull over by the side of the road to watch the storm from a safe place a couple of miles away, a distance where a storm looks like a discrete object the same way it looks like a discrete object on radar. Then after ten or twenty minutes we’d hit the road again, driving mostly-eastward to stay ahead of the storm. We stayed southeast of the storms, since they generally move east and northeast.

On our first evening, we didn’t catch any tornadoes. “Well,” Jim said, “at least let’s go see a rainbow.” I’d always thought of rainbows as an essentially random event, which I could only see by paying attention after it rained. But, of course, a rainbow has a cause: sunlight refracts through raindrops in the opposite direction to reveal the colors of the spectrum. The sun was setting, and the rain was moving east, so we drove to a spot west of where the storm had just passed. Sure enough, when we looked to the east, we saw a rainbow.

It was a little luck, but mostly just a simple causal understanding, and the decision to engage with the weather rather than passively letting the weather happen to us.

Jim has kept his old weatherman screen name over the years, as he’s made new accounts on new networks. Today he's pretty active on Twitter as @wxmann.

“That’s an interesting take,” Jim muttered to himself one morning as he thumbed through the Tweets on his phone. I’ve only ever heard this phrase in the context of political commentary, and I reflexively asked Jim what he was reading. He immediately started talking about wind patterns, temperatures, and dew points, all of which went over my head. “The upshot is that this guy thinks tornadoes will happen farther north this evening. I’m not so sure.”

Jim was reading Weather Twitter. Despite Zuckerberg’s consistent description of Facebook as “a community”, social media (including Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram) are less a single community than they are a substrate upon which different communities grow. On Twitter, whose public nature lends itself to interest-based groups, we get weird and wonderful niche communities, from the young queer opera fans of Opera Twitter to the avant-garde metafictional glitch artists of Weird Twitter to, yes, the storm-chasing, radar-watching meteorology nerds of Weather Twitter.

I let Jim weigh in on the forecasts and went down to enjoy the hotel’s complimentary breakfast. While eating my mass-produced omelette and sausage, I found myself watching a weather report on TV in the hotel dining room.

KANSAS HAS HAD A RECORD YEAR, the newscast declared. KANSAS HASN’T REACHED THE MONTH OF MAY WITHOUT A TORNADO SINCE 1980. COULD TODAY BE THE DAY?

I was struck by the difference in Jim’s explanations and the newscaster’s. Jim spoke in expert terms; the newscaster, in lay terms. The newscaster’s commentary was based the statistics of outcomes. Jim’s explanations were all about the causal dynamics of storms. Most importantly, the news made me feel like all I could do was speculate and gamble on the weather, where nothing more could be learned. Jim’s discussion made me feel the weather was something we could understand and grasp and make sense of, if only we dug deep enough.

As it turned out, our most successful evening of chasing tornadoes was in Kansas. We spent the afternoon in Great Bend, mostly on the lawn in front of the courthouse. Jim had tweeted an invitation to join us (tagged #wxtwitter), and we were soon joined by about a dozen other storm chasers from Weather Twitter.

The gathering must have appeared, to an outsider, similar to many other modern, mediocre social events — there was not much conversation, because everyone was staring at their phones. A closer observer, though, might have likened it to a football watching party, because they all were looking at (and commenting on) the same thing: weather radar and observations. Introductions and small talk were punctuated by chasers periodically commenting on a storm forming or turning towards an area with higher humidity.

Around 3:30, one of the storms to our south started picking up. One pair of storm chasers decided to pack up and head that way. Another group followed, and another, and suddenly Jim and I were sitting alone on the grass munching our snacks. I meekly asked the obvious question.

“Everyone else is gone. Should we head out, too?”

“Nah. I don’t like that storm to the north as much as the southerly one. More moisture farther south. That one’s closer to us, so we have some time.”

We eventually got in the car, me driving and Jim watching the weather radar and road maps to tell me where to go. We drove north for about an hour, then cut west until we caught sight of the storm. Finding a hill with a clear view, we pulled off the road to watch.

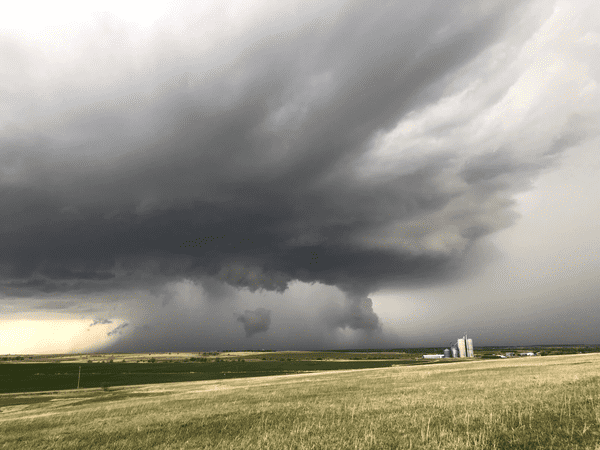

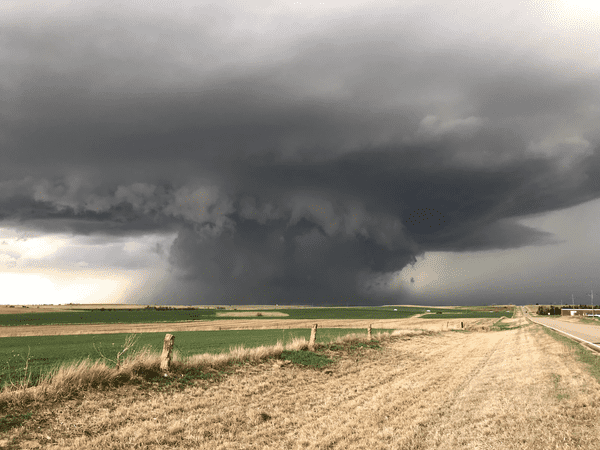

As the storm approached, we got back in the car and backtracked east, then cut north again, then continued east, periodically pulling off by the side of the road to get a better look at the storm. We were looking for rotation in the clouds, which naturally is a necessary precondition for a tornado. We kept tracking it for a couple of hours.

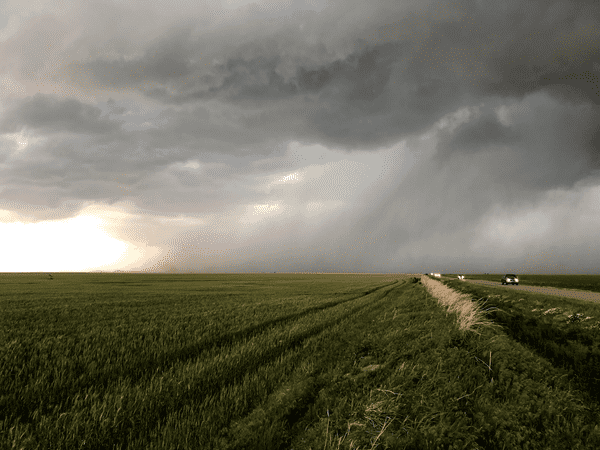

Finally, across the street from a gas station at the intersection of two highways, we and about two dozen other storm chasers caught this:

A funnel cloud had formed, the precursor to a tornado. I was breathless. The chasers by the side of the road were all cheering, watching, taking pictures. But after a couple of minutes, it dissolved, and with it, the small crowd that had amassed — they figured this storm was over, and were moving on to the next storm in hopes of seeing a stronger tornado.

Jim made the call: we would stay with this storm. “It still has a lot of energy,” he explained, “and, more importantly, it’s headed into a more humid zone where it can pick up even more energy.” We got back on the road, but instead of going north or south to the other storms in the area, we took the interstate east to get ahead of our storm again.

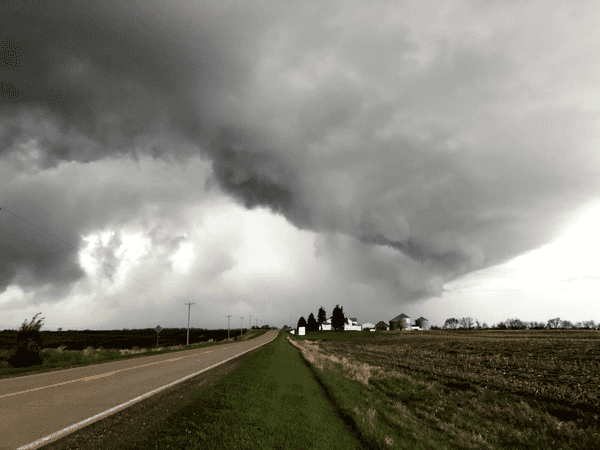

Our commitment paid off. We found a dirt road off of the interstate that went up a hill overlooking a field — a nice, clear view. Several other chasers were already here, including a few that we’d met in the afternoon. It was a good spot, and the right time, and soon a funnel cloud formed.

This one, too, quickly dissolved. The storm had gotten pretty close, so I was getting in the car to get out ahead of the storm again when Jim called me back to the hill to watch a second funnel cloud that had formed, which grew until it touched down:

Some of the other chasers whooped and hollered. I stood, silent and transfixed. A tornado is powerfully destructive, yet from a distance this one looked smooth and tranquil. As we'd seen just a moment before, a new tornado is delicate, and can fall apart just as soon as it forms. Watching a tornado touch down is a privilege, like watching a bird first take flight.

But we couldn’t stand around. In accord with Jim’s forecast, the storm was gaining energy as it moved east, and now it was moving much faster; meanwhile, we’d been in one spot gawking as the tornado passed us by. So we all piled into our cars and tried to keep up.

The most dangerous part of tornado chasing is driving. The roads are often wet, there’s sometimes debris from tornado damage, and — most surprising to me — these days the number of storm chasers driving to keep pace with a storm actually creates more traffic than the small country roads can handle.

Now that there was a confirmed tornado, a hundred or more storm chasers had converged on the spot, like when kids playing soccer ignore their positions and all clump around the ball. We had avoided the traffic thus far by staying ahead of the storm, but now we were in the thick of both weather and traffic.

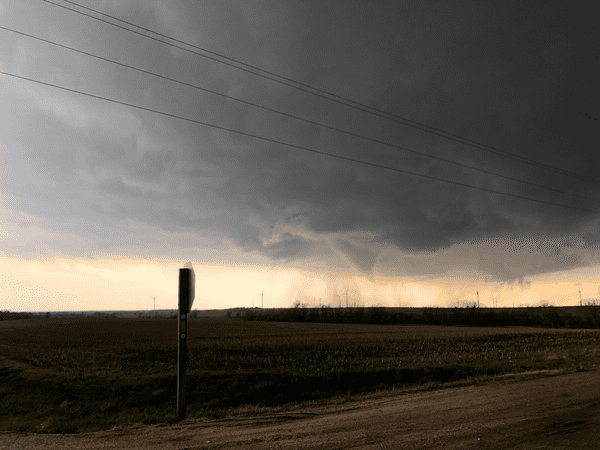

Unfortunately, as we trailed the tornado, the roads got worse. The only nearby eastbound roads were dirt roads, and we didn’t want to risk getting stuck in the mud, so we turned north, behind the tornado, and pulled over by the road to watch.

The tornado had grown from a narrow, almost cylindrical funnel into a huge wedge tornado — a vortex much wider than it is tall. Jim and I failed to get a good picture of this one, and honestly I don’t think any picture could do it justice. The tornado towered above us; the top of it covered half the sky. I had to crane my neck to see the entire tornado at once. It was like standing next to a giant walking the earth, and we weren’t even very close — probably a mile away. I felt small, vulnerable, and scared.

We started moving again, struggling to keep up with the storm, but we didn’t get another good look at it. Driving in its wake we saw some tornado damage: street signs that had been thrown into trees, downed power lines that we (and the whole line of storm chasers) had to gingerly drive over, and a plume of smoke from a fire, perhaps ignited by lightning strike.

(We looked up the damage report later, and, though there was some property damage, it seems nobody was hurt in this storm.)

We trailed that same storm for a while, and eventually the tornado dissolved. There was a chance that more tornadoes would form after sunset, but they're not much to look at in the dark, and we were pretty satisfied with what we’d seen in the day. We drove twenty miles to a big town, and treated ourselves to what Jim told me is a storm chaser tradition: a steak dinner.

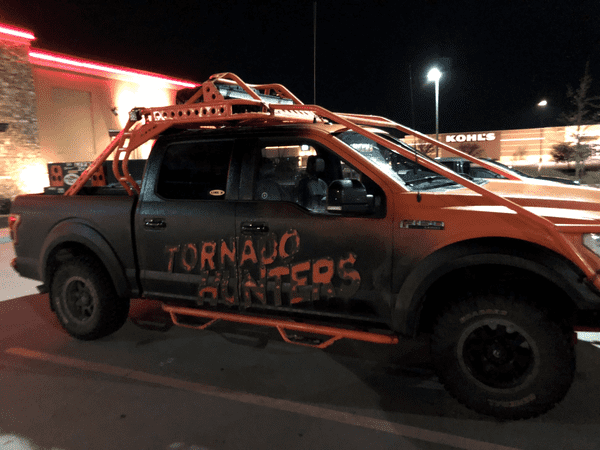

We weren’t the only ones. In the parking lot outside the steakhouse, we saw the two Tornado Hunter trucks, from the Netflix documentary. We were in good company.

The Tornado Hunters didn't get their own documentary by chance. Storm chasers understand storms and the weather, not as random statistical events, but as a system of causes and effects. With the zoomed-out perspective of weather radar, they recognize the storm as an entity they can engage and pursue.

And after a week of crisscrossing the Great Plains with my friend Jim, I've started to see it that way, too.